Writing Lessons from Roger Grenier’s palace of Books

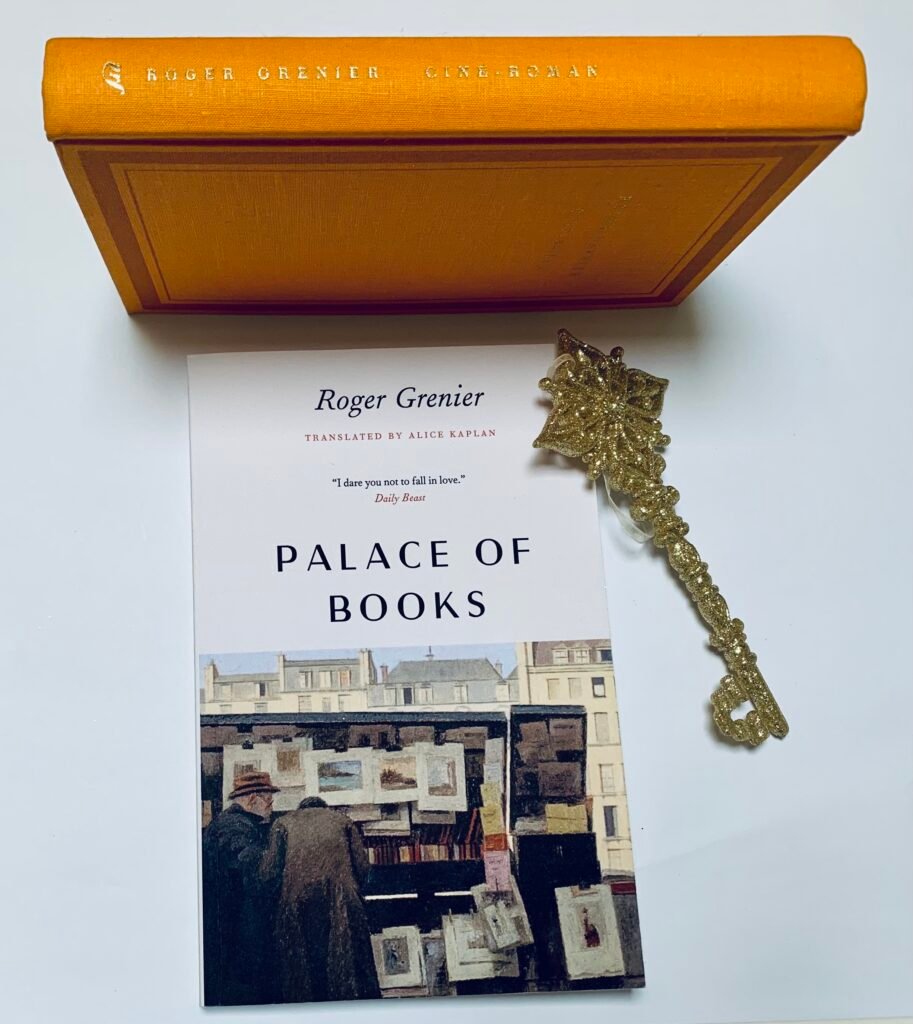

Lessons on the craft of writing begin at the entrance to Roger Grenier’s Palace of Books. The grandiose title suggests hefty tomes, big themes and museal features. Unsurprisingly, after a long erudite career in writing, Grenier explores big themes, but he presents them in nine short and accessible essays.

“Reality rarely unfolds with such pleasing logic.”

Palace of Books is just 150 pages long, including ten pages of works cited. The abundance of quotations and allusions to writers and their works (many of whom were friends and colleagues) illustrates the literary weight of the author’s remarkable life experience.

Grenier combines personal anecdotes and quotations from his predecessors and contemporaries to consider crime reports, short writing, the experience of waiting, author privacy, memory, unfinished works, suicide, love, and posterity from both reader and writer perspectives.

This book is for readers who enjoy philosophical reflections on the artistic and existential perspectives of writers. Big themes on writers of literary merit and their craft are examined through the lens of Grenier’s well-lived literary life.

Lessons

Lesson 1: Memory is a novelist

Writers have long understood the power of the subconscious to feed their imaginations. Grenier argues that “Memory itself is already a novelist.”

Virginia Woolf used memories of her parents when writing To the Lighthouse; Charles Dickens wrote about a long-held secret childhood trauma in chapter 10 of David Copperfield, and F. Scott Fitzgerald “couldn’t write without including his entire history.”

The persistence of memory is one of the main themes in Marcel Proust’s A la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Proust reflects on his life experiences in a search for the truth in this 7-volume novel (the longest novel ever published according to the Guinness World Records). Grenier relies on his memories of how his parents ran a local cinema in his Prix Femina award-winning novel Ciné Roman. Much of the narrative around the workings of the cinema is biographical.

If we examine our memories we have fully formed narratives often accompanied by analysis or commentary: “We know now that it is not a recording device, but that it is constantly recomposing the past.” Grenier adds that our memory invents more than it constructs and that “it is dynamic, nourished by our imagination, our personality, our passions, our wounds.”

He states that writing a book “devours memory” as the writer paradoxically saves and destroys those parts of the past that haunt them. By purging and recomposing those unsettling details from the past, the writer puts “life in its raw state” into a more emotionally coherent order that teaches readers something about the world and themselves.

Lesson 2: Readers love crime

In the essay ‘The land of Poets’ Grenier says that readers love to consume crime or “fait divers” (crime and related diverse human interest stories). He states that any crime report needs to be a “small novel” with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

However, Grenier reminds us that “Reality rarely unfolds with such pleasing logic.” This is as problematic as the details of the crime that usually unfold in gradual and confusing ways. And yet, reporters still manage to combine acceptable details and report a seemingly plausible and often entertaining story, at least for today’s news.

According to Grenier, the confusion lies in the “layer of concrete covering every motive, every attitude”. A writer faces similar challenges when beginning a novel. A reader is also discovering the details as they unfold from one page to the next.

The reality is that the details of most crimes unfold over minutes, days and even months or years. In the case of a novel, minutes are pages, days are chapters, and months or years are book sections. The writer must be satisfied that each page provides enough “pleasing logic” to keep the reader engaged.

Lesson 3: Readers love cliché

Grenier maintains that readers not only love the elements of a good ‘fait divers’ story, they also love the inevitable cliché within it.

Every newspaper is “a tissue of horrors” according to Charles Baudelaire (French poet, translator, literary and art critic). Grenier says that this absorbing material disgusts and fascinates the reader in equal measure. He refers to Marcel Proust’s (French novelist, critic, and essayist) admission of feeling “…a delightful sense of being once again in contact with that life with which, when we awoke, it seemed so useless to renew acquaintance.”

Grenier observes that most of the figures appearing in a crime story (fait divers) “conform to a well established role”. He recalls his work as a journalist writing crime stories in the middle of the night with little information other than the “wire service dispatch”. Grenier recalls that the crime stories were so common that borrowing elements from past stories, applying “the most ordinary rules of psychology”, and adding in “a discreet echo” of his “personal woes” sufficed in “convincing for the reader”.

Grenier compares the function of the fait divers and the novel: “Like the novel, the fait divers is designed to help people understand themselves.” In short, readers like to assess and judge other people’s mistakes.

About Roger Grenier

Roger Grenier (1919-2017) was a French journalist, writer, and editor. He was a prolific writer of novels, short stories, and literary essays.

As well as being a recipient of numerous prizes including the Grand Prix de Littérature de l’Académie Française, Grenier worked with Albert Camus at the newspaper Combat after he participated in the Liberation of Paris in 1944. He later wrote for France Soir and followed many post-war trials, one of which inspired his first essay Le Rôle d’accusé.

Grenier worked as an editor at Gallimard (a prominent French publishing house) for decades and edited some of the work of Albert Camus after he died in 1960. Le Palais Des Livres (Palace of Books) was published in 2011 when the author was in his nineties. It was translated into English by Alice Kaplan and published by The University of Chicago Press in 2014.